By Ted van Hooff

When you think of Green Heritage Fund Suriname, you think of sloths. Yet the foundation does more than rehabilitate this species. With educational trips, the GHFS team aims to show a new generation of Surinamese people that humans and nature need each other. I joined Geneviève, Cheyenne, Jonathan and Desiré for a weekend to see how this is done. Destination: Galibi.

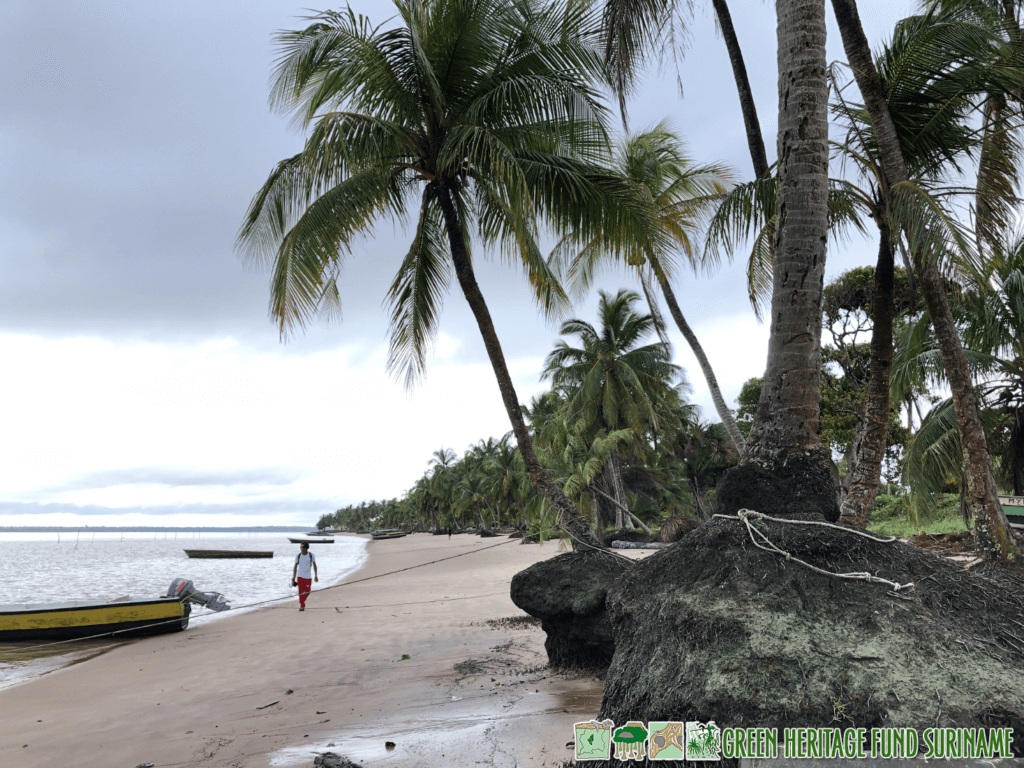

Galibi is located in the northeast of Suriname. From Paramaribo the bus takes us to Albina where we transfer to a wooden boat. The boatman covers our luggage with a plastic sheet. It can’t be that bad? Guess again. For an hour, the brackish water slaps us in the face. When the palms and fishing boats of Galibi appear in sight, we are soaked. We go ashore.

The coastal community consists of two converging villages: Christiaankondre and Langamankondre. There is a long stretch of sand between them. Palm trees, fishing boats and wooden buildings make up the landscape. It is quiet. Most residents live off fishing. Another source of income are tourists that come to Galibi to watch sea turtles. This weekend our focus is on Galibi’s youngest inhabitants. The thirty-four children that we will be working with are between six and eight years old.

After showing our face to the captain, we walk through the sand strip to a covered outdoor room. A group of eager children is waiting for us. That evening we play the animation film Finding Nemo. They impatiently slide in their seats as we set up the projector. The children double over with laughter when the seagulls throw themselves at Nemo and Dory.

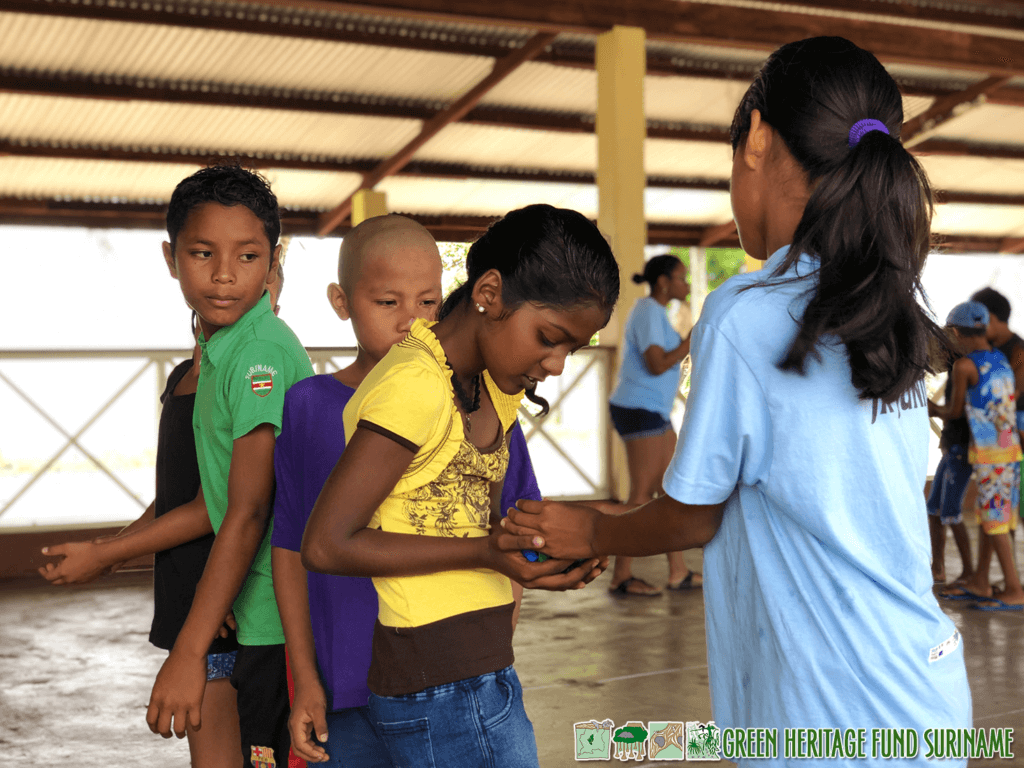

The next morning we return. The group of children has doubled. After a funny introduction game we get to the point: this weekend we hope to teach them how important it is to keep the ocean and the waters of Suriname plastic-free. On the floor, a life-size river that blends into the ocean has been drawn with chalk. At the mouth of each branch, children are waiting with a piece of plastic for the weather forecast that Jonathan is holding up. The sun shines? Then nothing happens. A heavy rain shower? Plastic waste washes into the ocean with high tide. So run!

Other games follow. Among other things, the children learn that you cannot blindly trust your senses if, for example, you want to find out the temperature of water. We end the day with a drawing competition and a plate of bami.

That evening, we find two green turtle hatchlings just outside our rooms. Just out of the egg, they have mistaken the porch light for the moon that leads them to the ocean. Their flippers are helplessly slapping against the concrete wall. We take them to the beach, where they bravely storm the high waves.

In each phase of their lives, sea turtles are confronted with challenges. Their nest are an easy target for raccoons, ghost crabs and dogs. For poachers, selling turtle eggs is an illegal but lucrative way of earning money. Once out of the egg, young turtles await high waves. Land and sea animals see them as an easy snack. Only a small minority of turtle eggs results in a mature turtle.

In the last decades, a new issue has arisen: plastic pollution of the environment. Animals consume plastic (parts) or become entangled in plastic waste, sometimes with fatal consequences. The small plastic bags that many stores give away for free, look like tasty jellyfish to a sea turtle. Plastic pollution is a global issue that poses a great threat to biodiversity, quality of life, and food safety worldwide. It also affects small communities like Galibi, which are directly dependent on the ocean for fishing and tourism.

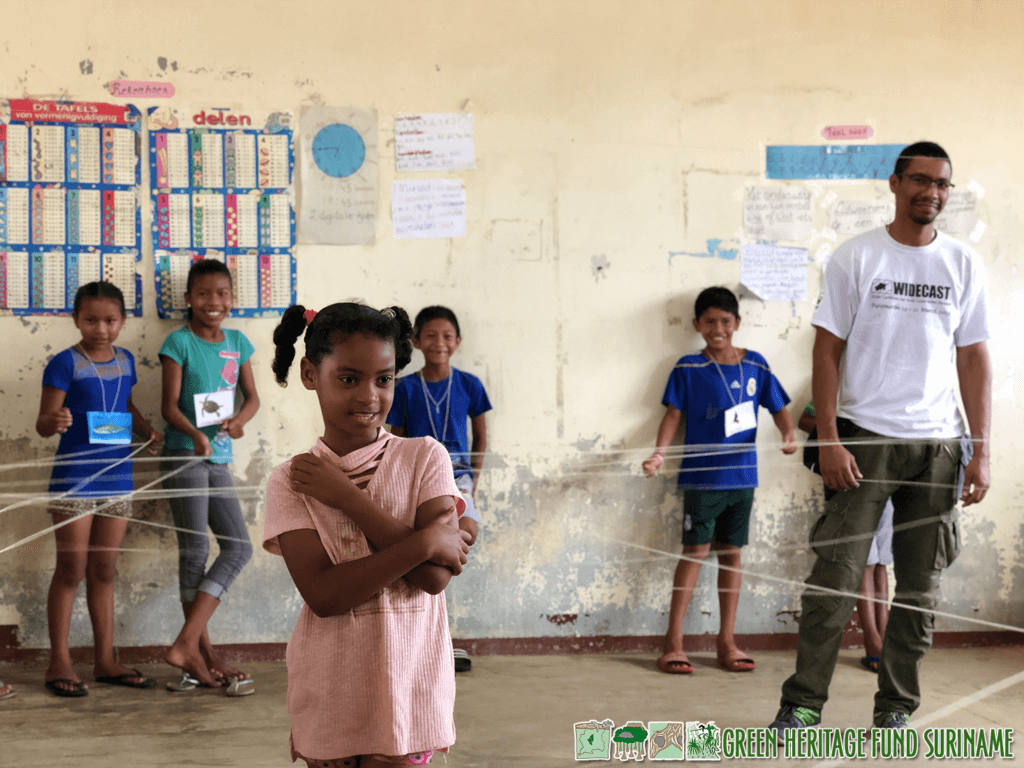

On Sunday morning, it is pouring and so we relocate to a classroom in the elementary school. The children form a circle. Each child has a string around their neck with a card that depicts a species: orca, turtle, whale shark, dog, etcetera. We connect each animal in the circle with a string of wool; together they form an ecosystem. What happens when the orca lets go of the string? The beautifully formed web slowly collapses – just like the ecosystem when a species disappears. When one species is struggling, the entire system suffers.

When the rain has gone, we go outside. The children can release all of their energy during the final game. Five paper hatchlings are attached to each child in one half of the group, while the other half takes on the role of predator.

Each group stands at the far end of the track that we have drawn in the sand. A few boys are practicing their shark moves. The hatchlings need to make it to the other side unharmed. The predators also need to make it to their opposite side, while making as many victims as possible by collecting the paper hatchlings.

When the whistle goes off, the track turns into a spartan battle scene. Paper hatchlings fly through the air, while others barely make it to the safe zone on the other side. After ten minutes, most of the hatchlings have perished. What have we learned from this? Hatchlings are very vulnerable to predators. Pollution by humans will only further complicate their struggle to survive.

This war of attrition marks the end of this weekend. Tired but satisfied, the hatchlings and predators spread to different parts of the town. They are going home. But first, they have an important question for us: When are you coming back?

They won’t have to wait long. Our next visit is scheduled for August. By returning regularly, we hope to raise awareness about the importance of a clean ocean. When we take the boat back, the sun is shining.