By Ted van Hooff

The sea and coastal area of the Guianas is home to many extraordinary animal species, among which are the Guiana dolphin, the leatherback sea turtle and the scarlet ibis. Compared to other parts of South-America, there is little information on local wildlife and the use of this area by its inhabitants. WWW Guianas, the Guianas’ Protected Areas Commission, Natuurbeheer and Green Heritage Fund Suriname have been working together since 2017 on Marine Spatial Planning an EU funded project to change this.

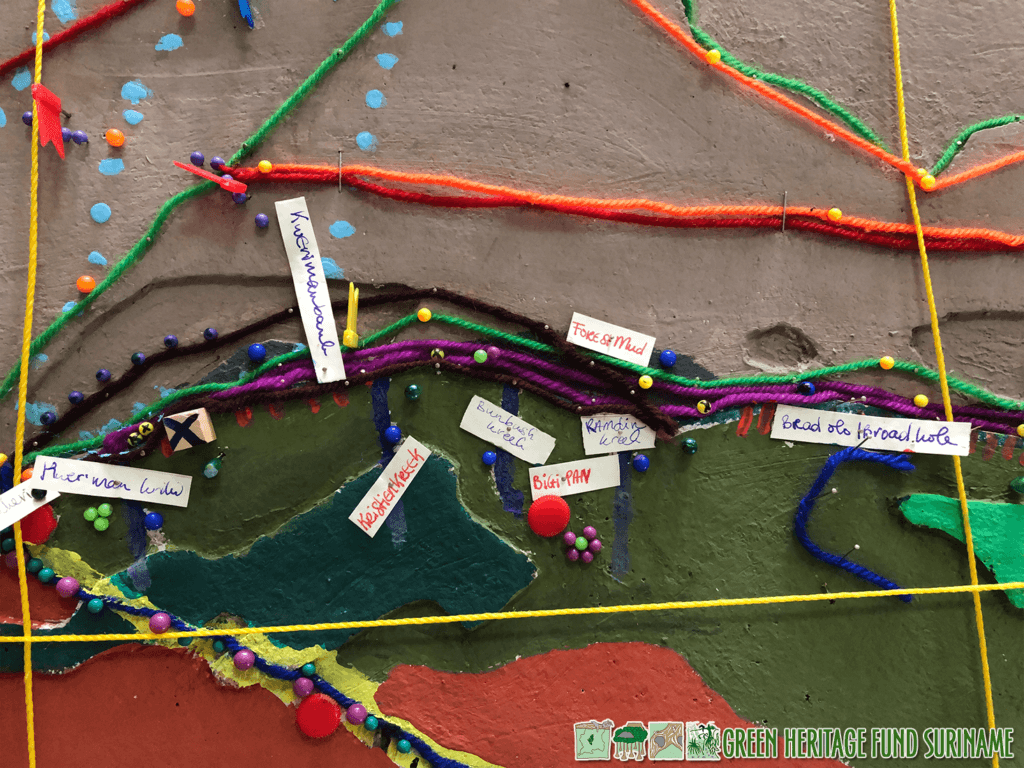

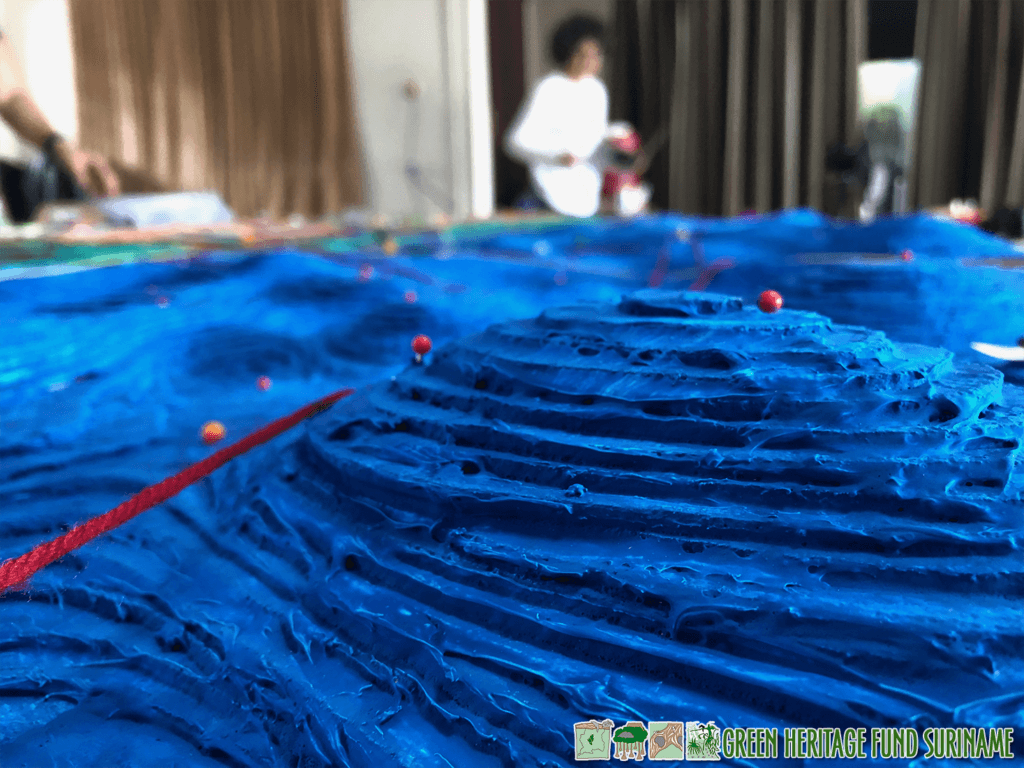

One of Marine Spatial Planning’s outputs is the creation of a participatory 3D model of the Surinamese sea and coastal area. The members of the consultancy team that is developing this model visit coastal villages and ask locals to share their experiences. The data the team collects is used for a three dimensional map that spans several meters and covers the coastal area between Nieuw-Nickerie and Galibi. To the north, the map extends 150 kilometers into the sea, to a water depth of 200 meters.

On a Thursday afternoon Monique and I visit the team. In a large room on Melaphier Street, Debora Linga, Sara Ramírez-Gómez and Tomas Willems are speaking with the captain of a local fishing boat. From an early age the man has been fishing in the entire area that is recreated on the map. Standing around the large, colorful landscape they listen to his story. He tells them where mud banks, whales and turtle nests are found. At the same time, the last pieces of the map are being colored with a paint brush.

I sit down with Tomas Willems. Tomas is from Belgium and has been working as a marine biologist in Suriname since 2012. “In 2017 we started with a base map. Blank, with only the coordinates, depth and height. First we visited the locals to ask what information they would like to see on the map. It is important to us that the information on the map is useful to them.”

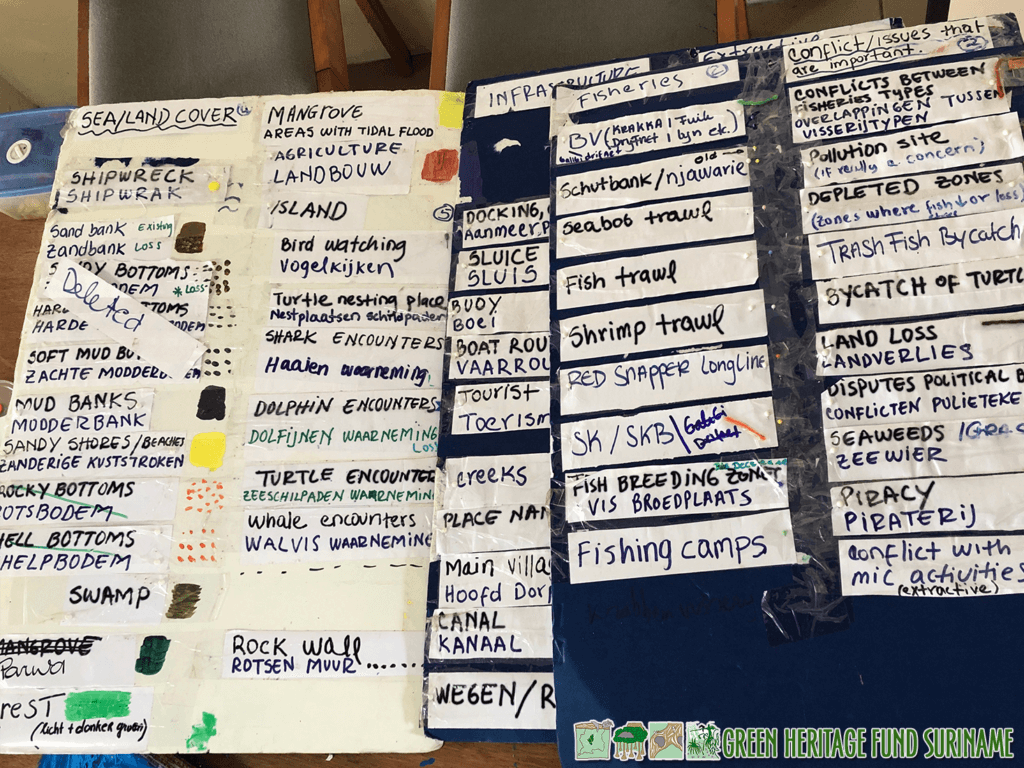

And so it happened. A single look on the map says a lot about the daily lives of these people. Thumb tacks and strings indicate sailing routes and bird watching locations. A red pin means severe pollution and a yellow one signals the location of a shipwreck. The use of trawls for catching fish and shrimp is marked by white thumb tacks. When you study the landscape closely, you keep discovering new things.

The map is built on multiple oblong tables that are pushed together into a large rectangle. The table legs are foldable, which is necessary, because the colossus travels to the coastal villages with Tomas, Sara and Debora by truck. “Initially, we wanted to make the map even bigger, but transport would then become impossible.”

The knowledge that locals pass on from generation to generation is a valuable addition to existing scientific information. Unlike scientists, the inhabitants of this coastal area have been living on this land and in these waters for decades. Before anyone else, they recognize patterns and changes in the landscape. Their stories therefore contain valuable clues for research.

“By now, we have talked to around sixty people of all ages,” Tomas says. “There appear to be more conflicts with regard to zoning than we expected. The boundaries of legal fishing areas, among other things, are often crossed.”

The captain confirms that not everyone abides by the rules. Regularly he comes across cages that are placed on the seabed for catching red snapper. Because such cages are often lost and then continue to trap fish, it is a prohibited fishing technique in Suriname. Nevertheless, the technique is frequently applied, resulting in damage to the fish stock. The area also has to contend with poaching. Turtle eggs turn out to be lucrative merchandise and many nests are raided within 24 hours. If nothing changes, the future of sea turtles in Suriname is uncertain.

The map is digitized at the end of May and sent to all interviewees for a final check. The end result will be presented to a large audience in June. The collaborating parties of the Marine Spatial Planning process funded by the EU hope the map will lead to new insights for policy makers. They can create policy that ensures that the coastal area will continue to be liveable for humans and animals in the future.