Suriname is home to two species of sloth, the three-fingered Bradypus tridactylus and the two-fingered Choloepus didactylus. Although neither species is currently considered threatened with extinction [12, 13] , their well-being and health is threatened to varying degrees by many activities in different parts of their range.

DEFORESTATION

Both the three and two fingered sloths are arboreal, so deforestation is one of the largest activities threatening their survival [2, 10]. Suriname’s expansive forests are threatened by urban and agricultural expansion, as well as by the timber, mining, and oil industries. Clear-cutting can greatly affect sloths, and in one instance, deforestation of a 6.8 hectare urban forest patch in Paramaribo negatively impacted 135 sloths, all of which had to be rescued and relocated. This process of this habitat destruction and handling by humans lead to behavioral changes including increased aggression, fear, and restlessness [46], which are symptoms of stress and reduced welfare (Broom, 2010).

Deforestation has many potential negative impacts on welfare. First, loss of habitat also corresponds with a reduction in food availability, either by removal of food or forceful relocation into an area where individuals must find new sources of food [39]. Prolonged malnutrition, starvation, and dehydration significantly reduces animal well-being and health, causing suffering and disabling them from performing other important behaviors [35]. B. tridactylus, due to its low dispersal capabilities [28], sedentary and slow-moving nature, small home range, and tendency to stay still instead of fleeing when faced with danger, is even more impacted by deforestation. C. didactlyus moves more quickly, is more aggressive, and has better dispersal abilities, so they can better adapt to habitat modification [39]. But, individuals of both species can be injured, killed, or forced to quickly adapt to a new environment, which can reduce welfare. Additionally, B. tridactylus has more specialized requirements for habitat, requiring intact forest areas with connected canopies and heterogenous vegetation [40]. Two-toed sloths are more flexible when it comes to habitat, but they will also avoid clear-cut agricultural areas [28].

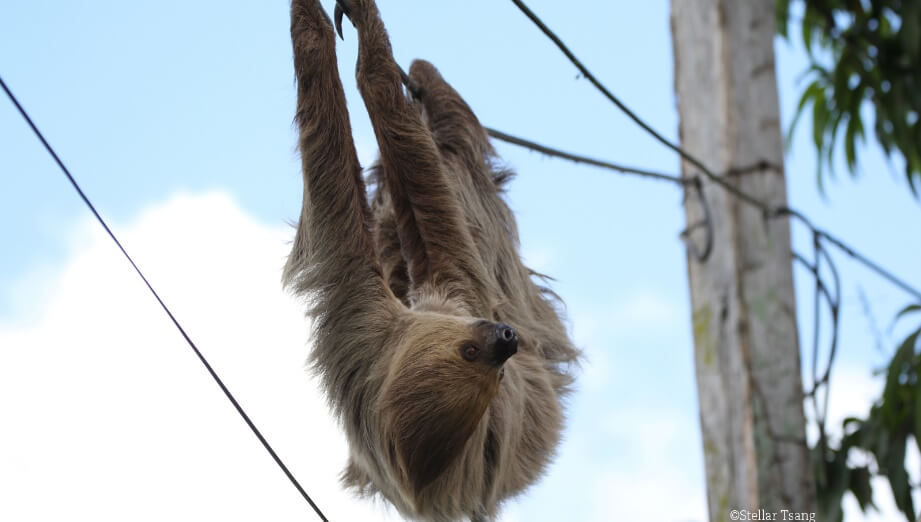

Even if animals survive the clear-cutting process without injury, they face further problems in establishing a new living territory. Deforestation can force sloths into environments they’re not adapted to survive in, like agricultural or urban landscapes. In these new environments, they face threats of starvation and dehydration, with additional threats of cars, human interaction, and electrocution in urban environments [39]. Since many of adult sloths rescued by GHFS are found in the urban areas of Paramaribo, it is important to consider what drives these animals to an inhospitable environment. Even if a forest is only partially clear-cut, new fragmentation can alter forest resources and lead to edge-effects, which pose unique challenges for an animal to adapt to [56]. An important factor in considering wildlife welfare is ensuring that species can exist under conditions to which they’re adapted to [25], which habitat loss compromises.

Conservation efforts that are meant to save sloths from these fates, like rescue and relocation, also come with unfortunate welfare strains. Rescue entails handling, manipulation, and transportation, which can cause stress and agitated behaviors for sloths [46]. Relocation, although to an environment better suited for their survival, can also pose temporary welfare problems for many different animals as they become acclimated to their new environment [37], establish territory and find a reliable source of food. So, although rescue missions are an effective way to protect sloths, the best way to eliminate poor welfare and stress is to prevent habitat loss.

PET TRADE

More and more, sloths are advertised in media as being very gregarious animals, which creates a demand for sloths in the pet trade. Several animals that end up in the care of GHFS come from being kept in captivity as pets, which causes an observed reduction in their health and wellbeing. Wildlife pet trade causes a great deal of suffering for many species of animal, as they are often transported in inadequate housing, potentially causing injury or asphyxiation, and are not provided with adequate resources, leading to malnutrition, dehydration, and starvation [5]. As already noted, the process of handling and collecting wild sloths can often cause them stress and lead to non-typical behaviors indicative of fear and aggressiveness [46].

If sloths survive the trip, more problems wait for them at their destination. Sloths can experience a lot of health problems in captivity. In a study testing the clinical problems captive sloths experience, sloths coming from living in private homes are often significantly malnourished, likely due to their dietary specificity which makes them difficult to feed, especially the three-fingeredBradypusspecies [18]. Complications from improper feeding has been noted in the baby sloths that later come under the care of GHFS, particularly in a young two-fingered sloth received in early June of 2018. This animal couldn’t digest the inappropriate food given and her stomach contents entered her lungs, threatening her life. Sloths also commonly experience pneumonia and other respiratory problems when they are subjected to improper temperature and humidity regulation in their housing. Sloths are adapted to a high temperature and humidity climate due to their low thermoregulatory capabilities and slow metabolism, and can suffer under colder conditions [18].

While in captivity, sloths can also be harmed in other ways by their caretakers. With a very strong grip and long claws, sloths can have their nails cut or filed, as well as their teeth. The lack of information on how to best treat these animals, in regards to their diet, environmental needs, and behavior, is what leads to such suffering, sickness, and stress in captivity [39].

HUNTING

Hunting is another significant threat to B. tridactylus andC. didactylus [2] who are hunted and consumed throughout their range, including in Suriname. Although not the most hunted Xenarthra species or most popular to eat [59], sloths, historically, have been hunted for bushmeat by indigenous communities throughout the neotropics [50], although the hunting of sloths is not limited to these communities. Sloths are not a legal export in Suriname [23], so hunting occurs for internal personal consumption or small-scale internal trade [61], although the data is lacking.

Hunting can cause poor welfare in any hunted animal in instances where the attack is not initially fatal. If not killed immediately, an animal can experience stress and pain for minutes, hours, and even days. If the injury is severe, it can prevent the animal from performing life sustaining behaviors, like seeking sustenance and avoiding predators, leading to further suffering from starvation and malnutrition [55]. For a slow-moving animal like the sloth, the impact of an injury on mobility may be even larger.

In several instances, it was observed or suspected that the mothers were hunted for food while their babies were initially kept as pets before ending up in the care of GHFS. This can cause reduced welfare for the baby on top of the problems that come with pet trade. Sloth babies spend all their early life clinging to their mothers and learn a lot of motor and behavioral patterns from them. Orphan babies are more likely to consume harmful flora and objects and have motor and behavioral abnormalities [58]. Separation from their mothers can also cause babies significant stress, causing them to elicit a distress call in the form of a whistle or bleat [38].

Therefore, although not the most pressing threat to sloth conservation in Suriname, hunting can have a significant impact on welfare and development.